Differentiating media from The Media

In my last post, we covered the origins and evolution of the different mediums that make up the media landscape. While it was an interesting history lesson, I’m sure many of you are more interested in the specifics of the media of today and I promise we will take this Deep Dive in that direction. But as always, I sincerely believe that context is everything when it comes to developing a nuanced understanding of these big ideas. So before we go after The Media or what you may recognize as Mass Media, let’s start small and work our way up. You’ll quickly see just how interwoven all media have become in the digital age of the 21st century.

The first level or classification of media I’d like to recognize is called ephemera.

The word ephemera comes from the Greek “ephemeron” meaning lasting only one day. [Ephemera] has been described by scholars as “minor transient documents of everyday life” and “a broad range of minor (and sometimes major) everyday documents intended for one-time or short-term use.

-Library Company of Philadelphia

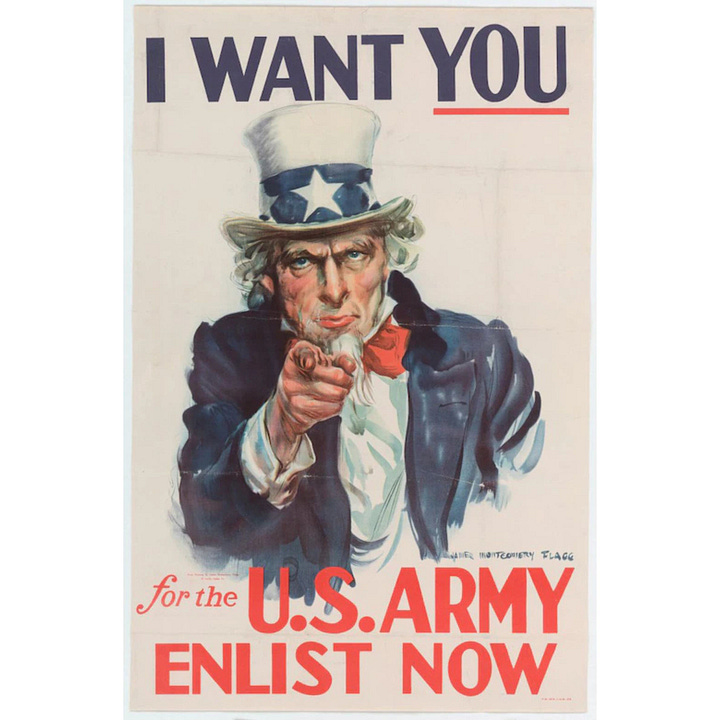

Some examples of ephemera include: Grocery lists, movie tickets, receipts, menus, newspapers, greeting cards, posters, letters, memos, and notes. These items are seemingly insignificant to what we traditionally consider media and communications but they are quite integral to the functioning of everyday life. Oftentimes, they end up rumpled in the bottom of our purses and pockets, catching wind and tumbleweeding down the street, or gone forever in the bottom of a trash bin. But when preserved either on purpose or accidentally, they are often the most interesting bits of media in helping us understand everyday life.

Ephemera marketed for, found, and displayed in homes serve as benchmarks of popular culture and provide evidence of the changing role of the consumer and consumerism as well as social [behaviors over time]. Additionally, playbills, tickets, keepsakes and souvenirs, menus representing and promoting events, excursions, and performances record how early Americans spent their leisure time and money. Notices for public meetings and Civil War recruiting posters, and official proclamations reflect the sociopolitics of their day. All of the aforementioned represent a range of historical printing and graphic art processes, trades, and designs, as well as mirror the conscious, unconscious, and historical biases and prejudices of the society in which they were generated and received.

-Library Company of Philadelphia

If you are someone who holds on to your travel tickets, collects posters, flyers, or other pamphlets of interest, welcome letters, or college acceptances - you know, other people’s junk - you are collecting ephemera. If you’ve ever discovered a box of such items in your grandparents’ attic or dug up a time capsule you can appreciate how these small items make you feel connected to the past and the people who came before.

The next classification of media I’m going to explore is Personal Media. What I am referring to here are media that are significant to us and longer lasting - but don’t necessarily have a large audience in mind when we create them. This range can include diaries, journals, scrapbooks, photo albums, home videos, family newsletters or email chains, letters, Christmas cards, and beyond. They are often created to only be consumed by the creator and their immediate circles. In the last 15 years, this has expanded to include social media.

Looking back at the history of blogging, journaling, and diary practices, [scholars] see similarities between how people are now using [social media]. “I had always thought of diaries as these little notebooks with locks on them into which you pour your innermost thoughts. This is a very modern notion of diaries.” Throughout most of the 19th century, [we’ve now] discovered people would share their diaries, either sitting down together or mailing back and forth. Friends and family would write in the margins, creating an element of interactivity. Young women would leave their homes to get married and send diaries home as a means of maintaining relationships. Diaries were essentially a social practice of communication.

-Bailey Karfelt, Cornell University

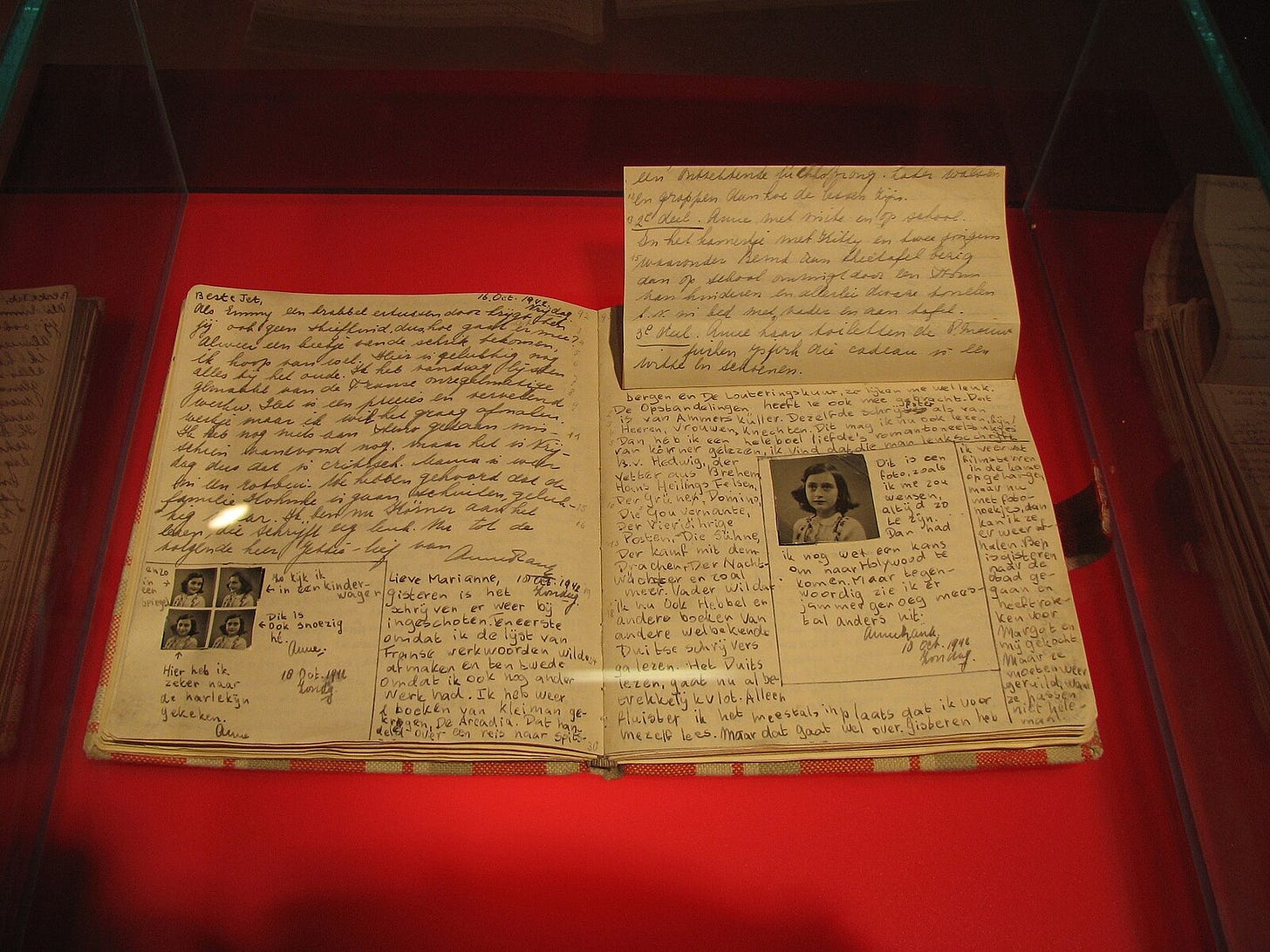

Perhaps two of the most famous examples of Personal Media that have been made public are “Diary of a Young Girl” which is more famously known as “The Diary of Anne Frank” and Marcus Aurelius’s “Meditations.” Frank received her journal as a thirteenth birthday gift in 1942. Shortly thereafter Anne’s mother was ordered to deliver herself to a Jewish labor camp by order of the German army but instead remained with her family who went into hiding. The family sequestered in a small space Anne’s father had hidden behind his office bookshelf.

For two years, Frank wrote dedicatedly in her journal of life hidden behind the office walls. She wrote faithfully and consistently before she was captured in 1944 and sent to a concentration camp where she would die of Typhus the following year. The journal was discovered and returned to her father, the only surviving member of the Frank family, after the war and liberation of the camps.

The meditations of Marcus Aurelius chronicle his private musings during his time as Roman Emperor between the years 161 and 180 AD. A follower of the Stoic movement of philosophy, Aurelius wrote his way through the nerves and stresses of being Emperor. This highly intimate look into the mind of one of history’s most powerful leaders is oftentimes no more than fragmentary thoughts. At other times it is comprised of incredibly well-reasoned arguments. Scholars still look to these writings as a source of answers for many of today’s challenges such as anxiety and depression. Through his writings, Aurelius worked to quiet his mind as he held history in his fist.

Many of Rome’s Emperors were incredible orators and philosophers. Speech was considered an important part of their role as many rose to power through impressive demonstrations of military and political leadership. This collection of writings however is generally accepted as having been intended only for personal use and was likely never meant to be shared with the Roman public. It was only posthumously that the writings were compiled into a book called “Meditations” and can now be purchased at most bookstores 1,845 years after their origin.

Fast forward and we see the same behaviors that came naturally to Frank and Aurelius persisting as part of the human experience. The reality is that the majority of social media users are using these platforms as a means of documenting their own lives whether or not they also keep diaries or journals. Celebrations, travels, milestones, and memories are all accounted for on Facebook, Instagram, X (Twitter), and the rest. While Big Media, celebrities, influencers, and corporations do use these platforms to communicate with and pander to thousands, even millions of people around the world, most of us are still using the sites as digital scrapbooks. For the masses, their online communities are still relatively similar in size to their in-person social networks.

Just beyond the cusp of our social circles are our Communal Circles. In this tier of communication, we aren’t just tied to those we personally know or have loose connections with, but those who belong to our larger communities. From our neighborhood to town, city, county, and all the small communities we join in between, these groups incorporate us sometimes without our active participation.

You may identify as part of a religious organization that extends beyond the reach of people you know well. It could be all the students on your large college campus or alumni association. Maybe you are part of a community theater troupe or a local sports league. The media used to communicate here can vary in audience size but extends beyond our immediate circle while still catering to a specific rather than public audience.

This is often the first place we begin to ask questions about sources and fact-checking as we don’t always know where or who the information we are receiving comes from. These are people who may have different values, interests, and backgrounds from ourselves - hence not fitting in our close-knit groups - yet share enough of a tie to require group communication either via community boards, online groups, large email networks, or even digital and paper newsletters - “the oldest form of mass media predating newspapers.” Fans of Bridgerton may be thinking of “Lady Whistledown” whose community would be members of the ton (elite society) but not the entire country. Your modern-day example might be a local newspaper or county-wide email for things like road or school closures that only addresses people in that particular locale.

Once we break beyond this barrier of perhaps no more than a couple thousand people we are firmly in the territory of Mass Media.

Mass media is mass communication whereby information, opinion, advocacy, propaganda, advertising, artwork, entertainment, and other forms of expression are conveyed to a very large audience. [Generally] mass media have included print, radio, television, film, video, audio recording, and the Internet.

-Brian Duignan, Encyclopaedia Britannica

The form of mass media we are probably most familiar with is Broadcast Media. Broadcast media is the most traditional form of mass media and is defined as:

A form of mass communication that involves transmitting news, entertainment, and information via television and radio to a wide audience. It is characterized by its reach and immediacy, making it a powerful tool for influencing public opinion and providing real-time updates. Key components of broadcast media include television networks, radio stations, and digital streaming services, all working to deliver content through various platforms.

-Vaia Digital Education

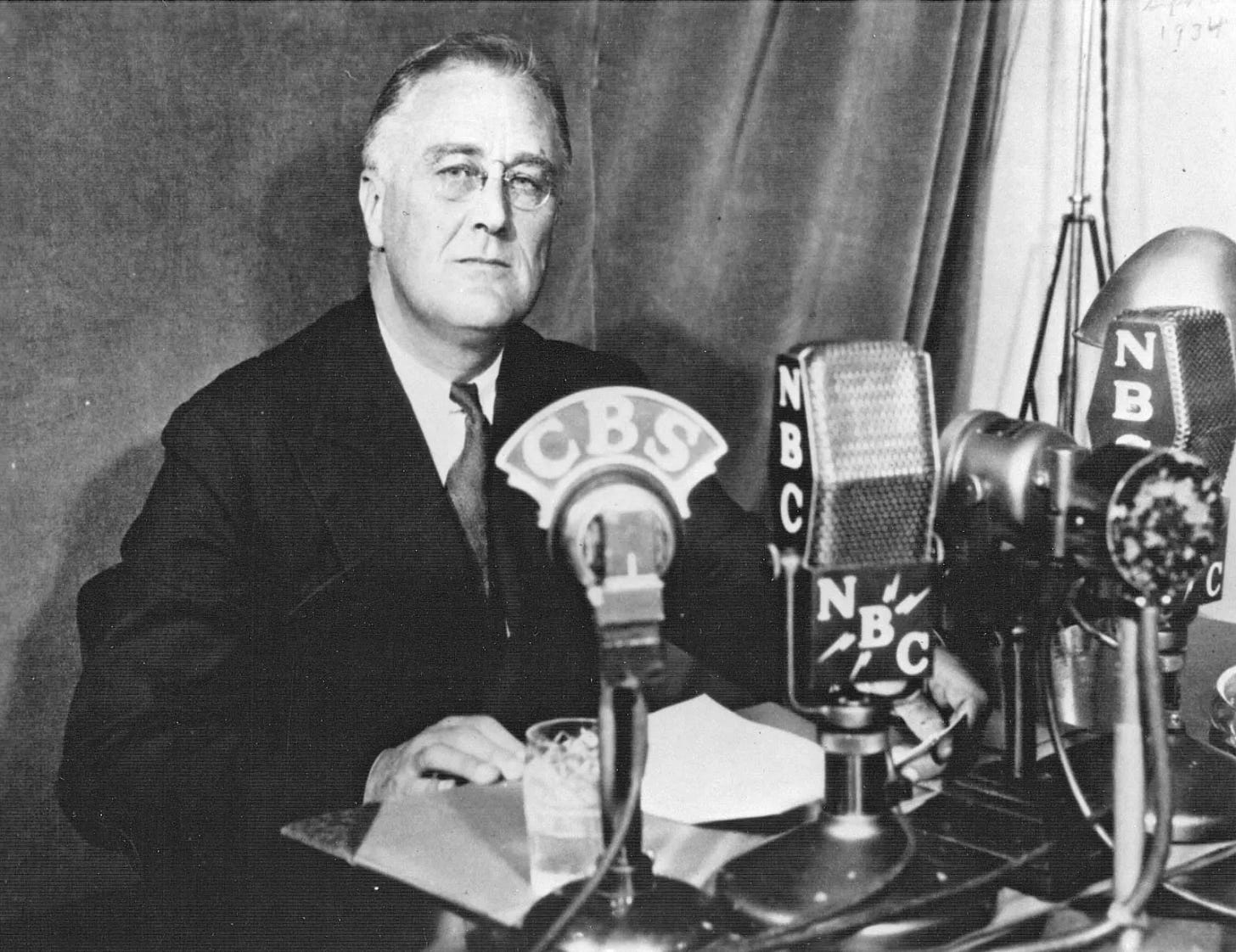

The very first radio broadcast in America took place on Christmas Eve, 1906. Out of Massachusettes the broadcast featured two musical selections and concluded with the reading of a poem. It wasn’t until 1933 however that the most famous historical example of radio broadcasting in America would begin. These broadcasts, led by then President Franklin D. Roosevelt, would be come to known as the fireside chats.

From 1933 to 1944 President Roosevelt regularly used radio broadcasting to speak directly to the American people. This was the first time in United States history that the head of state participated in direct and ongoing dialogue with the citizenry. The purpose of these broadcasts which coincided with The Great Depression and Roosevelt’s New Deal Era was to win the support of the American people during a period of great uncertainty. Because of the havoc and despair that spread through the nation during that era of depression, Roosevelt became and still is the President to have signed the most executive orders, and exercised the most direct control over the nation’s direction.

In an attempt to get things back on track and pull America out of its economic slump, Roosevelt introduced his New Deal policies and even broke the two-term precedent set forth by America’s first president, George Washington. Roosevelt knew he was standing on shaky ground and decided to use radio as his way of reassuring the populace. Ultimately, this plan was incredibly successful and these chats have an enduring legacy of inspiring hope and faith in the American people. It is an incredibly important reminder of the power of communication and the role it plays in maintaining faith between Americans and their leaders.

If we jump ahead to the Presidential Election of 1960 we see another huge advancement in the role of broadcast media in American politics and culture. On September 26th, 1960, the first debate in that year’s presidential election campaign was broadcast on CBS to an audience of about 70 million Americans. It’s crucial to note that this is the first-ever instance of a televised presidential debate. That is, this is the first time that presidential candidates were seen and not just heard as household figures. It also cemented the ties between politics and popular culture.

This first televised debate took place between the young up-and-coming senator of Massachusettes, John F. Kennedy, and the seasoned Republican presidential nominee and current Vice President, Richard Nixon. Even today, 65 years later, the legacies and images of these two politicians and former presidents could not be more different. And in the moment, it seemed their images, quite literally, were going to be perceived radically differently as well.

Immediately following the debate it was clear to political correspondents that something strange had transpired amongst the American people. In interviewing the populace it was discovered those who had listened to the debate on the already much-used radio felt strongly that Vice President Nixon had won the debate. But those amongst the 70 million who had tuned in on their television sets felt strongly that Kennedy was the clear winner of the debate. An interesting conundrum.

In the years that have followed the same explanation for this divide persists. It seems the harsh reality was that television, in a single night, had revolutionized communication forever by adding image to sound.

Television was changing the political process and how one looked and presented oneself on TV was more important than what one said. This seemed to be the case during the first debate. Younger, tanned, and dressed in a dark suit, Kennedy appeared to overshadow the more haggard, gray-suited Nixon, whose hastily applied makeup job scarcely covered his late-in-the-day stubble of facial hair. [In short] many believed that Kennedy won the election because he won the first debate and that he won the first debate because he looked better on TV than his opponent.

-Steve Allen, Robert J. Thompson, Encyclopedia Britannica

At this moment, optics quite literally became everything.

Now when we look at the state of American politics we can see the lasting effects of both of these major firsts on mass media. What we also see are a million different modes of control working behind the scenes to better shape and control the messages broadcast in our direction. Having learned invaluable lessons in communication from both of these powerful events, The Media has worked to guide the opinions and feelings of the American people. While it has largely worked to continue inspiring and bringing hope to the people as was Roosevelt’s intent, it has often failed repeatedly to maintain that trust and loyalty. Never before has that been more apparent than now when new media is constantly interjecting in the places where legacy media has reigned dominant.

The easiest way to distinguish between new and legacy media is simply that new media is mainly comprised of digital/internet-dependent news sources while legacy is more closely linked to traditional/old media sources that originated in broadcast. When people chastise or lament the failings or corruption of “The Media” or in the last ten years complain about “Fake News” they are usually picturing old media. Generally speaking, this is because it feels tangible and less anonymous than more emergent forms of media like that found on social platforms. By tangible I mean there is someone to point a finger at, someone - or rather some company - to hold accountable. In a sense, The Media becomes a scapegoat for all of the uncertainty that circulates in these rather uncertain times. But as we’ve been discovering, these big news sources aren’t the only ones providing media coverage to us regular people at home.

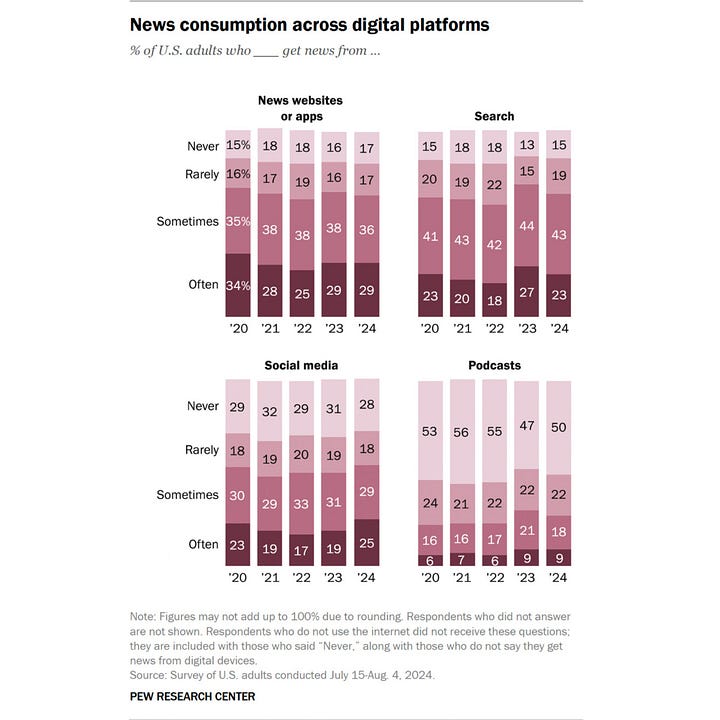

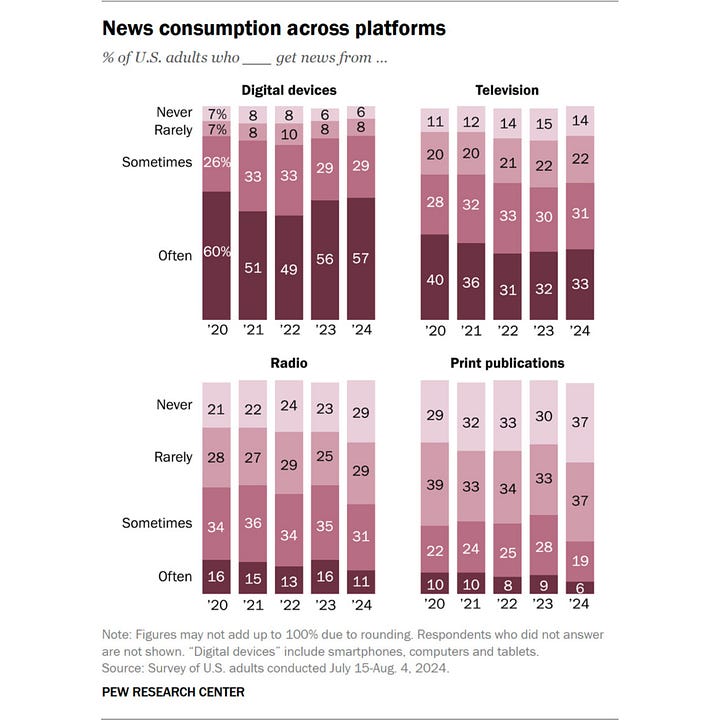

Studies conducted by The Pew Research Center show that by the middle of 2025, social media will be the dominant source of news in America.

But social media posts aren’t fact-checked and regulated by rigorous journalism practices. While many may be checking the accounts of these legacy news sources, there are far more casual sources that are delivering their two cents directly into the hands of a mass audience. This majorly affects our understanding of what mass media is. While not everybody with a massive reach on the internet speaks with journalistic intent, many do. Whether it be politics, economics, international relations, disaster, or other breaking news topics, the average person now has the ability to deliver their own opinions, researched or not, to millions. For many, this is an exhilarating and addictive source of power. For many others, it occurs by accident via algorithmically driven virality.

While many believe this level of competition with formalized sources serves as an encouragement and quality control factor that ensures journalists are sharing the correct information promptly, others fear it opens the doors to an unmanageable onslaught of misinformation. This debate over who is more informed, or rather who is more honest, the people or the media, has endured for years. But just as the government is supposed to be by the people for the people, the press too has historically operated under similar guiding principles. As we move forward, the reliability, accuracy, and integrity of The Media will continue to undergo close examination.

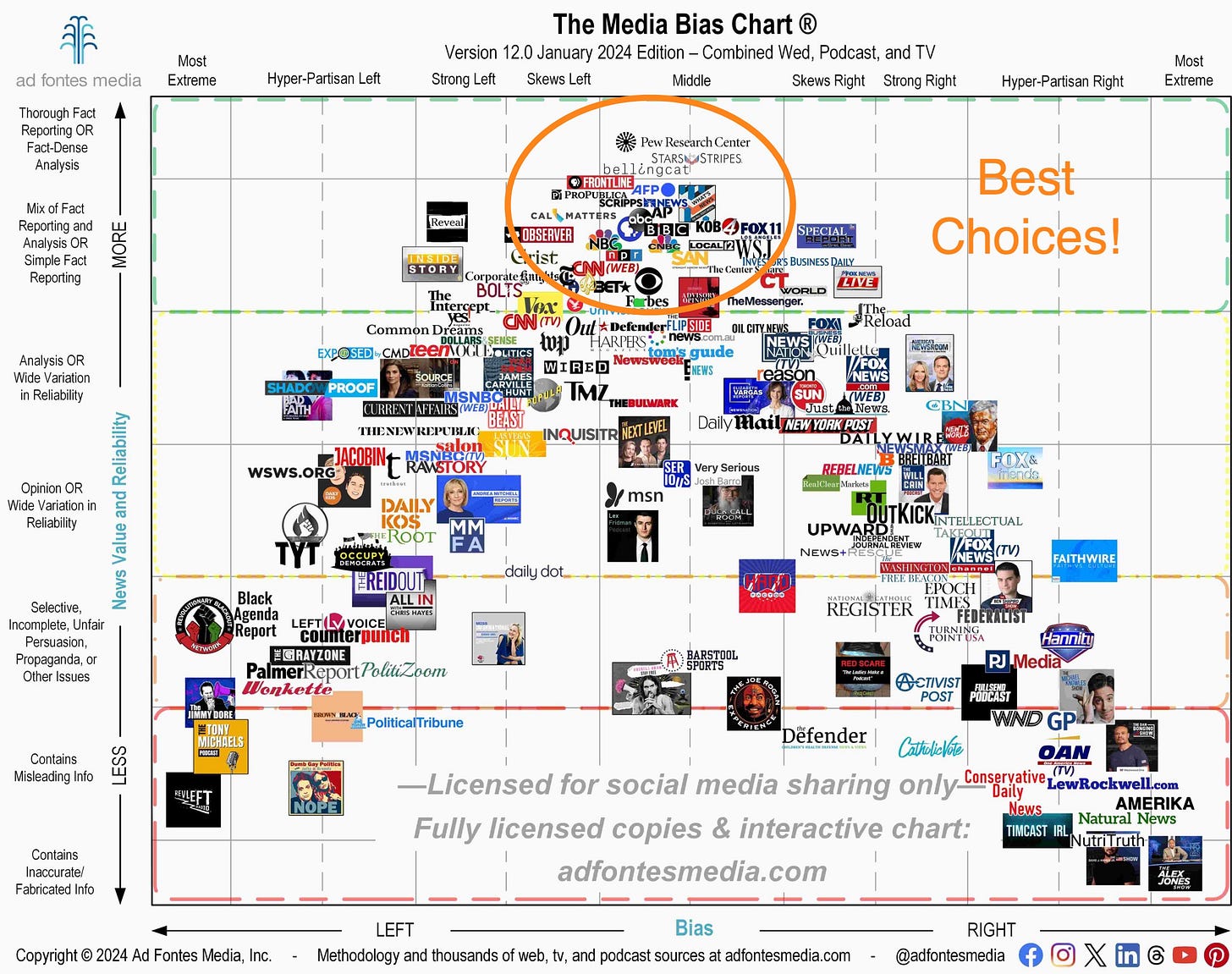

If you are uncertain where to look for guidance I am going to share a graphic which is updated annually for accuracy. This graphic will show you exactly which sources of mass media are the most reliable and reputable. It accounts for accuracy, professionalism, and bipartisanship. I highly suggest that when choosing news sources from The Media, you stay as close to the center line as possible, and only trust sources at the top of the chart.